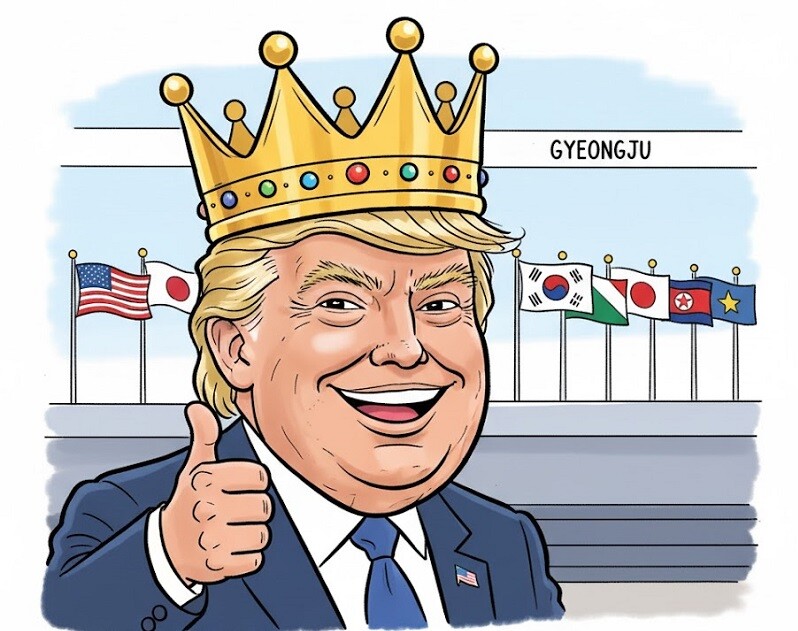

In Gyeongju on Tuesday, U.S. President Donald Trump responded with a broad smile as he received a golden crown from South Korean President Lee Jae-myung during a ceremony held on the sidelines of the APEC summit 2025. The unusual diplomatic gift, modeled after an ancient Silla gold crown, immediately drew worldwide attention: Why did South Korea present a crown, and what does it symbolize?

To understand the gesture, it is necessary to look beyond modern politics and into the deep layers of Korean history. The crown evokes the memory of Silla, an ancient Korean kingdom that once flourished on the same ground where Trump stood. Silla ruled the southeastern part of the Korean Peninsula from roughly 57 B.C. to A.D. 935, making it one of the longest-lasting dynasties in East Asian history. It was a powerful maritime and cultural kingdom that traded with China and Japan, developed advanced goldsmithing, and built a sophisticated aristocratic culture. Archaeologists and historians often describe Silla as the “golden kingdom,” a reference to the extraordinary quantity and craftsmanship of gold artifacts unearthed from its royal tombs.

The Silla gold crown is the most iconic of these treasures. Often found in royal burial mounds around Gyeongju, the ancient capital, the crown is considered one of the most refined pieces of goldwork in the ancient world. It is delicate, lightweight, and built with extraordinary precision, constructed from thin hammered gold sheets and adorned with small dangling ornaments. Unlike the heavy metallic helmets associated with European kings, Silla crowns were ceremonial, symbolizing authority rather than serving as armor. They were placed on the heads of kings and queens during ritual events, funerary rites, or moments intended to display divine legitimacy.

The structure of the crown carries meaning. Tree-shaped vertical ornaments represent a sacred world-tree linking heaven and earth, while antler-shaped branches reference shamanistic beliefs and animal spirits associated with protection and leadership. Small comma-shaped jade pieces, known as gogok, hang along its edges. In Korean culture they symbolize life, fertility, and eternal fortune. To ancient Silla, the crown was not merely jewelry: it was a statement of cosmic order, political stability, and spiritual power.

In the 20th century, when royal tombs in Gyeongju were excavated, archaeologists discovered several crowns crafted with pure gold, sometimes weighing over a kilogram despite their filigree-like delicacy. These discoveries stunned global historians and challenged assumptions that the Korean Peninsula lacked an advanced metal culture in antiquity. Today, original Silla crowns are housed in the National Museum of Korea and the Gyeongju National Museum. The museum district of Gyeongju, designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, remains one of the most important archeological spaces in East Asia.

That is why the golden crown presented to Trump carries symbolic weight. It is not an archaeological artifact, but a specially made replica inspired by the Silla originals—an item rarely offered to a foreign leader. South Korean officials described the gesture as a cultural tribute and a diplomatic message, an effort to celebrate forty-plus years of the Korea-U.S. alliance while highlighting the peninsula’s ancient heritage. The government stated that the crown represents a “golden era” of partnership between Seoul and Washington, emphasizing that the alliance is not a temporary military arrangement but an enduring historical relationship.

The presentation also arrives at a politically sensitive moment. Trade negotiations between the United States and South Korea have been tense, with discussions involving tariffs, supply chain cooperation, and semiconductor policy. Cultural diplomacy has often softened these sharp edges, and Seoul has frequently relied on tradition and symbolism when dealing with international leaders. In this context, the crown is a tool of soft power: a reminder that diplomacy is not only written in treaties, but also in gestures.

Still, the gift has sparked debate in South Korea. Some protesters gathered near the summit venue holding signs that read “No Kings,” arguing that giving a crown to a controversial political figure could be interpreted as legitimizing a monarchical image. Online discussions also questioned whether the symbolism aligned too closely with Trump’s well-known affinity for displays of power. Yet others defended the decision, claiming that the symbolism pointed not to an individual but to the alliance itself. For them, the crown was cultural pageantry, no more and no less.

Foreign experts say that this type of symbolic diplomacy is not unusual. Countries often present historical reproductions—samurai swords from Japan, medieval tapestries from France, or indigenous carved masks from Canada—to express respect and regional identity. The key is that the gift must carry cultural authenticity. In that sense, a Silla-style crown is one of the most culturally recognizable objects South Korea could offer. For an international audience unfamiliar with the peninsula’s ancient past, it is also an invitation to learn.

If Trump’s reaction—smiling, nodding, and joking about trying it on—was any indication, the message was received warmly. How it will influence policy is unclear, and diplomatic symbolism does not replace negotiation. But for a moment, in a city of tombs and gold, international politics and ancient history briefly merged. Whether celebrated or criticized, the gift has succeeded in doing what cultural diplomacy is designed to do: spark conversation far beyond the borders of Korea.

SayArt.net

Jason Yim, yimjongho1969@gmail.com