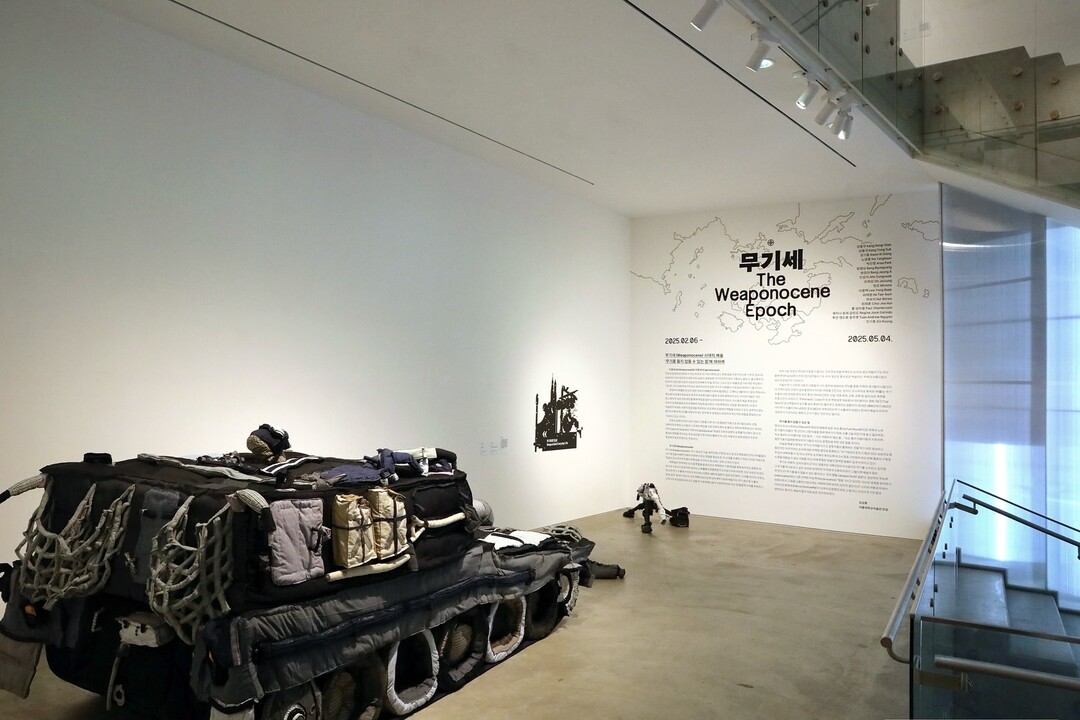

The Seoul National University Museum of Art (MoA) presents The Weaponocene Epoch (무기세 武器世), a large-scale exhibition that critically explores the pervasive influence of weapons in contemporary life. Featuring 18 artists from Korea and abroad with over 120 works, the exhibition runs until May 4, challenging visitors to reflect on the militarization of daily life, media, and the global economy.

The term Weaponocene is coined by the museum, drawing inspiration from the Anthropocene and Capitalocene, which describe humanity's environmental and economic impact. This exhibition suggests that the 21st century is defined by weapon production, military-industrial expansion, and war-driven technological advancements, shaping our world in both visible and invisible ways. Through a range of mediums, the exhibition reveals how weapons infiltrate not only battlefields but also consumer culture, entertainment, religion, and personal identity.

The works on display transform ordinary objects into military symbols, exposing the hidden violence embedded in daily life. Heo Bo Ri’s Soft K9 and Soft M2 reshape business suits and ties into tanks and firearms, symbolizing how corporate structures parallel military hierarchies. An Seong Seok’s video piece Unstoppable Alarm Sound disrupts conventional narratives of war memorials, overlaying the sound of bullet casings with an alarm clock, underscoring how violence is normalized in everyday life.

Another striking feature of the exhibition is the way weapons are transformed into visual spectacles, mirroring their portrayal in news, films, and social media. Choi Jae Hoon’s My Historical Wound Series records the act of firing live bullets into stainless steel mirrors, distorting the viewer’s reflection to question how violence shapes personal and collective identity. Lee Yong Baek’s Angel-Soldier presents camouflaged soldiers hidden within floral landscapes, symbolizing the way war is masked and aestheticized in modern media.

The exhibition also critiques the commodification of war imagery in consumer culture. Noh Young Hoon’s Mickey repurposes the iconic Disney figure into a gas mask, while M3 Campbell Soup transforms Andy Warhol-inspired soup cans into landmines, demonstrating how war imagery, once a warning, has become a marketable and consumable aesthetic. These works highlight the disturbing reality that violence has been woven into everyday consumerism.

The final section explores the long-term impact of military expansion and technological warfare. Jin Ki Jong’s Warrior of Freedom presents two hyperrealistic sculptures of soldiers—one from the U.S. Special Forces, the other an Al-Qaeda fighter—facing each other in tense confrontation, raising questions about the ideological structures that sustain perpetual conflict. Regina José Galindo’s video Shadow captures the artist fleeing from a German-made Leopard tank, symbolizing the way developed nations profit from global arms sales while fueling conflicts in war-torn regions.

Other key works include Oh Jae Sung’s Memory of Sculpture, which connects generations of Koreans affected by war, dictatorship, and democratization, and Bang Jung Ah’s Surviving Among Nuclear Zombies, which uses the imagery of nuclear-contaminated zombies to metaphorically critique the lasting effects of nuclear warfare. These pieces collectively explore how weapons shape not only geopolitics but also individual lives, memory, and the environment.

The Weaponocene Epoch runs until May 4 at the Seoul National University Museum of Art. Curated tours are scheduled for February 26, March 26, and April 24 at 2 PM, providing audiences with deeper insights into the exhibition’s themes. With free admission, the exhibition serves as a crucial platform for reflecting on the role of weapons in contemporary society and the hidden violence within our daily lives.

Sayart / Nao Yim, yimnao@naver.com