For a long time, robots were built to work.

They were designed to lift, sort, assemble and replace human labor. Speed, accuracy and efficiency were their purpose. A good robot was one that did not fail.

But in art spaces today, robots are doing something very different.

They are slow. They wobble. They hesitate. And people stop to watch them.

This shift was already imagined decades ago by Korean video art pioneer Nam June Paik.

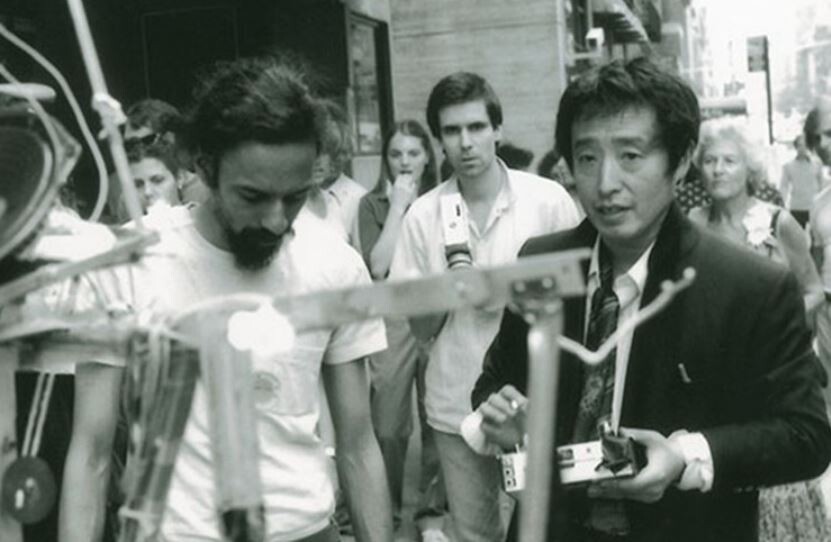

In 1964, Paik created “Robot K-456,” a human-sized, remote-controlled robot that barely functioned by industrial standards. It needed several technicians just to move for a few minutes. Paik once joked that while robots were meant to reduce human labor, his robot only increased it.

But that was the point.

Paik was not interested in building a useful machine. He was interested in building a human one.

Recently, “Robot K-456” returned to the stage after decades of silence. Restored and reactivated, the robot moved again — stiff, awkward and fragile. It did not perform a task. It did not solve a problem. Instead, it performed presence.

And the audience responded.

Unlike factory robots designed to disappear into productivity, Paik’s robot demanded attention. People did not ask what it could do. They asked what it meant.

This reaction helps explain something larger happening today.

We now live in a world filled with highly advanced machines. Yet the robots that attract the most emotional attachment are not the strongest or smartest ones. They are the ones that talk back, pause, mispronounce words or show simulated feelings.

Emotional AI, companion robots and virtual idols are growing in popularity not because they are efficient, but because they feel incomplete.

Humans tend to project themselves onto what feels fragile.

A perfectly functioning machine leaves no room for imagination. A shaky one does. When a robot hesitates or moves awkwardly, it creates space for empathy. We begin to read intention into motion. We see ourselves.

This is why virtual K-pop idols and digital characters are gaining loyal fans. Their appeal does not come from realism alone, but from narrative. They are not workers. They are performers. And in some cases, they become emotional partners.

In this sense, robots are no longer competing with humans. They are reflecting them.

Nam June Paik understood this early on. In 1982, he famously staged a performance in which “Robot K-456” was hit by a car outside the Whitney Museum in New York. He later called it “the first catastrophe of the 21st century.”

It was not a prediction about technology failing. It was a statement about human anxiety.

Today, robots have not taken over the streets. But people are forming emotional bonds with machines in ways Paik anticipated. The question is no longer whether robots can replace us.

The question is why we are drawn to machines that seem as uncertain as we are.

Technology continues to advance. But human affection remains unchanged.

We still prefer machines that feel a little broken.

SayArt.net

Jason Yim yimjongho1969@gmail.com