Two Buddhist paintings that vanished from a temple in Daegu nearly three decades ago have finally returned to Korea. Their journey reflects not only the persistence of Korea’s Buddhist community but also the broader challenges of protecting and reclaiming cultural heritage.

The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism confirmed on Thursday that it had received the Yeongsan Hoesangdo (The Assembly on Vulture Peak) and the Samjang Bosaldo (Bodhisattvas of the Three Worlds) from a Japanese holder who inherited the works and voluntarily donated them. The paintings, created in the 18th century, were stolen from Yongyeon Temple in late 1998 when thieves cut the wooden rods securing them in place. For 27 years, their fate remained unknown.

The Yeongsan Hoesangdo, painted in 1731, is especially significant. It portrays the Buddha preaching on Vulture Peak in ancient Magadha and marks the first confirmed case of monk Seoljam serving as suhwaseung, or lead painter, in a temple project. Assisted by monks Pogeun, Segwan, and Seolsim—artists active at prominent temples such as Tongdo, Jikji, and Mihwang—the work also bears a rare connection to royal patronage. Lady Cho Bin-gung, consort of Crown Prince Hyojang and daughter-in-law of King Yeongjo, was a sponsor. This is the only known case of her supporting a Buddhist temple project, lending the piece both artistic and dynastic importance.

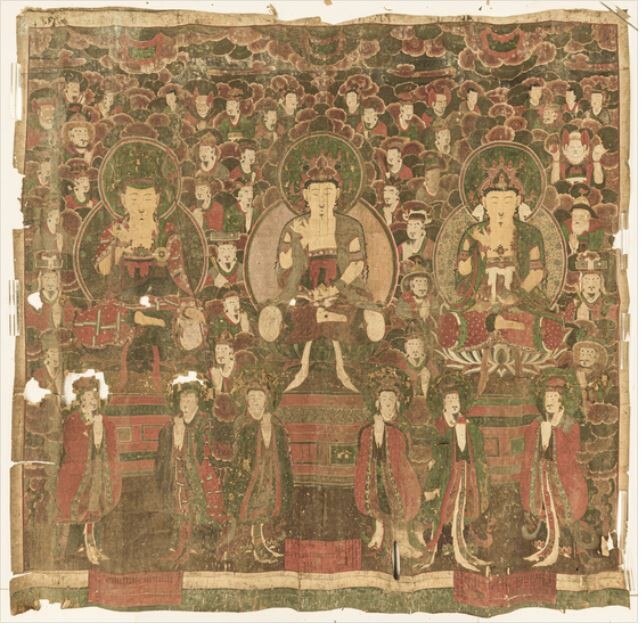

The Samjang Bosaldo, completed in 1744 by monk Sutan and others, depicts the three cosmic guardians: Cheonjang Bosal of the heavens, Jiji Bosal of the earth, and Jijang Bosal of the underworld. Its style follows the lineage of Chejun, a disciple of Uigyun, whose own works at Donghwasa Temple in Daegu influenced a generation of Buddhist painters. By altering the depiction of Cheonjang Bosal and adding more attendant figures, the painting advanced both composition and iconographic expression, signaling shifts in 18th-century Buddhist visual culture.

The theft in 1998 devastated Yongyeon Temple and the broader Buddhist community. For decades, the Jogye Order publicized the loss, hoping for leads. That persistence paid off this March, when a Japanese individual who had inherited the works from his father reached out. “I thought it best to return them to their rightful place, as they are sacred treasures and part of Korea’s cultural heritage,” he said, according to the order.

At Thursday’s handover ceremony, Venerable Seongwon, head of the Jogye Order’s cultural affairs department, expressed gratitude. “The donor realized the works were stolen and showed goodwill by ensuring they could return to their original temple. We thank him for this act of conscience,” he said.

The Jogye Order dispatched experts to Japan to verify the authenticity of the paintings before accepting them. After clearing customs, the works were transferred to the preservation center in Yangpyeong. Both had sustained damage from the theft and years of private storage and will now undergo professional conservation.

The return of the paintings is not just a recovery of lost property but a reaffirmation of identity. Buddhist art in Korea is both devotional and communal, embodying centuries of religious practice, artistic skill, and patronage networks that included monks, aristocrats, and royalty. When such works are stolen, the rupture is not only physical but spiritual, cutting communities off from a lineage of faith and memory.

Cases like this also highlight the ongoing debate over cultural repatriation. Around the world, artworks displaced by war, colonization, or theft remain in private or foreign collections. Each successful return—whether through diplomacy, legal action, or voluntary donation—adds momentum to global discussions on heritage justice.

For the Jogye Order, the recovery of the Yeongsan Hoesangdo and Samjang Bosaldo is both a moral vindication and a cultural victory. “The recovered paintings are of national cultural heritage value,” the order said. Their return is a reminder that even after decades, cultural treasures can find their way back home—when conscience and history align.

SayArt.net

Kelly.K pittou8181@gmail.com