Korea’s latest proposal to UNESCO — the nomination of Naebang-gasa and early modern Korean dictionary manuscripts — is more than an administrative submission. It is an appeal to recognize two bodies of work that hold profound historical, cultural and human significance. These collections do not simply illustrate how Koreans wrote their language; they reveal who was allowed to write, who risked everything to preserve that right and how a nation defended its identity through letters on a page. For these reasons, both should be inscribed without hesitation on UNESCO’s Memory of the World International Register.

The first collection, Naebang-gasa: Songs of the Inner Chambers, captures an extraordinary literary tradition created by women from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century. In an era when women were largely excluded from public life and formal education, these handwritten works — 567 pieces that survived — formed an alternative cultural sphere in the interior rooms of Korean households. Through these texts, women voiced everyday joys and grief, personal struggles, moral reflections and, at times, sharp social criticism. Their voices, long marginalized in official historical records, emerge here with clarity and dignity. The corpus is not only a testament to women’s literary creativity, but also to the democratizing power of Hangul, which allowed non-elite and non-male writers to document their experiences. Inscribing this collection would affirm the global importance of preserving women’s intellectual history, especially in societies where their contributions were historically overlooked.

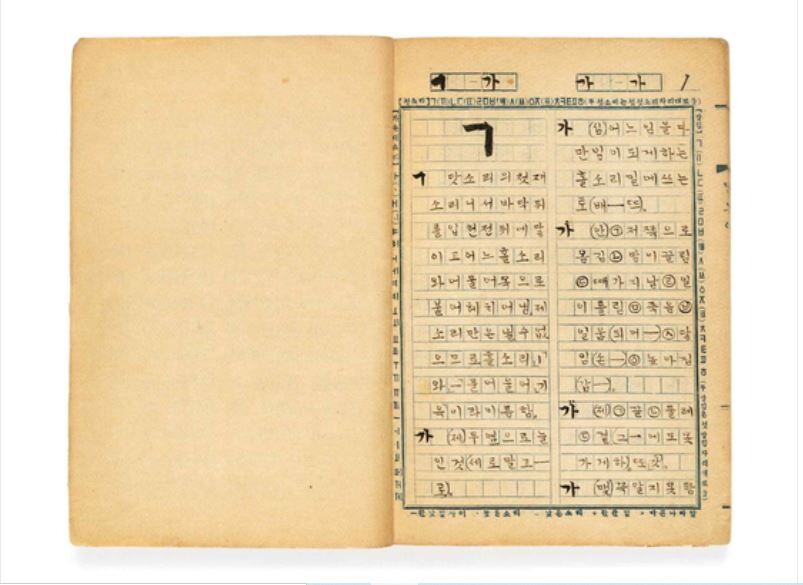

If Naebang-gasa represents the intimate and domestic, the second nomination occupies the opposite end of historical experience: resistance in the face of cultural suppression. The surviving volume of Malmoe, compiled by Ju Si-gyeong and Kim Du-bong between 1910 and 1912, alongside 18 manuscript volumes of The Comprehensive Korean Language Dictionary, embodies the determination to safeguard the Korean language under Japanese colonial rule. These works were created at a time when the future of Korean linguistic identity was increasingly uncertain. Scholars raced to record, classify and unify the national language, believing that losing it would mean losing the soul of the nation itself. These manuscripts are not simply lexicographical documents; they are historical evidence of intellectual courage and a collective movement to protect the mother tongue. Their inscription would underline the universal importance of linguistic preservation during periods of political oppression.

UNESCO’s Memory of the World program aims to protect irreplaceable records that hold outstanding universal value. Both Korean collections meet this standard. They are rare, authentic, deeply informative and central to understanding the evolution of literacy, identity and cultural resilience. They show how language becomes a site of empowerment for the marginalized and a battleground during colonization. They expand our global understanding of how societies document themselves — not through royal edicts alone, but through the quiet labor of women, scholars and ordinary citizens.

Korea already has 20 entries on the UNESCO register, from the Hunminjeongeum to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, each reinforcing the country’s long-standing commitment to preserving knowledge. Adding Naebang-gasa and the dictionary manuscripts would complete the narrative arc: from the creation of the Korean alphabet, to its everyday use by women, to its defense under colonial threat.

At a time when global languages vanish rapidly and historical memory is increasingly fragile, safeguarding these archives is not just a matter of national pride. It is a duty to future generations. UNESCO should recognize these two collections for what they represent: the survival of a people’s voice, written in their own script, carried across centuries by those who refused to let it disappear.

SayArt.net

Maria Kim sayart2022@gmail.com