Among the many figures who shaped modern Korean art, few retain the emotional gravity of Lee Jung-seop (1916–1956). His life unfolded against the backdrop of colonial rule, war, separation, and relentless poverty, yet the art he produced remains filled with tenderness, vitality, and the aching beauty of longing. For many Koreans, Lee Jung-seop is not merely a painter from history but an artist whose works seem to carry the crisp light, wistful silence, and melancholic warmth of autumn itself. His lines feel like falling leaves, his colors like fading afternoons, and his subjects—bulls, children, families—like fleeting memories preserved before winter sets in.

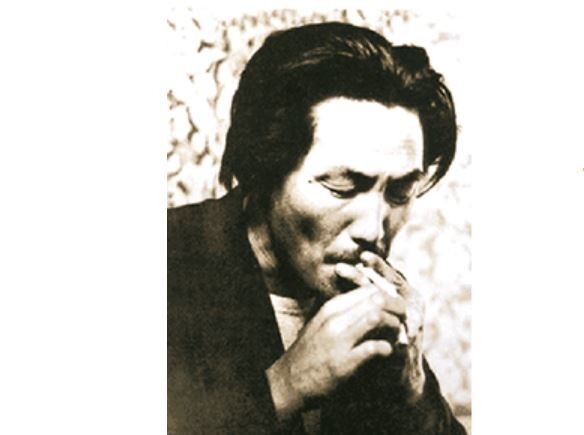

Lee was born in Pyongyang in 1916 and spent his youth in a Korea under Japanese occupation. His artistic journey took him to Tokyo’s Bunka Gakuin, where he encountered Western modernism and met his Japanese wife, Masako, whom he affectionately called Yuni. Their marriage, both tender and turbulent, would later become one of the most poignant threads in his life and in the mythology surrounding him. Returning to Korea, Lee moved from city to city in search of safety and stability during the Korean War. Economic hardship forced him into makeshift studios, and he often painted on whatever surface he could find—including cigarette foil, resulting in the now-iconic silver-paper drawings that reveal both desperation and brilliance.

Despite living through some of the harshest years in Korean history, Lee’s artwork radiates an emotional clarity that still moves viewers today. His famous bulls, drawn with thick, pulsing strokes, embody both his inner strength and his inner turmoil. His images of children, inspired by his two young sons, seem joyful at first glance but reveal a father’s heartbreak in their distance and fragility. Even his landscapes, often rendered in muted browns, ochres, and grays, evoke the quiet beauty of late autumn—rich, subdued, and reflective.

This year, Korea has renewed its attention to his life and work through a dedicated archival showcase titled “Lee Jung-seop Archive Exhibition Part 3: 1952–1954.” The exhibition focuses on a pivotal period marked by war-time displacement and emotional upheaval. It presents rare books, photographs, letters, and other documents that illuminate the personal circumstances behind many of his best-known works. Held at the Lee Jung-seop Exhibition Space—located within the Creative Studio Gallery on Lee Jung-seop-ro 33—the exhibition runs from September 5, 2025, to February 1, 2026, and is open daily from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Visitors are drawn not only by his artwork but by the intimate traces of his life: handwritten notes, portraits of his family, and photographs showing the precariousness and passion of his journey.

Lee Jung-seop’s short life ended in 1956, when he died alone in a small Seoul hospital, weakened by illness and malnutrition. His wife and children were living in Japan at the time, and the separation—financially unavoidable yet emotionally devastating—remains one of the most tragic chapters in Korean art history. Yet in the decades since his passing, his reputation has only grown. Streets and museums have been named after him, and his exhibitions continue to draw long lines. The modest number of works he left behind has achieved near-mythic status in the Korean consciousness.

Koreans still remember Lee Jung-seop for reasons that go beyond mere artistic achievement. His life embodies the struggle and resilience of a nation that endured colonization, war, and division. His art, with its trembling lines and urgent sincerity, speaks directly to the emotional core of Korean identity. His devotion to his family, expressed through letters filled with sketches and longing, touches audiences even today. And his tragic, misunderstood life has given rise to a cultural narrative that often compares him to Vincent van Gogh—a solitary genius whose brilliance was more fully recognized after his death.

Above all, Koreans continue to treasure Lee Jung-seop because his work feels profoundly human. His art carries the emotional temperature of a season when beauty and sorrow coexist. Autumn in Korea is a season of quiet truth—of clarity, longing, and memory—and Lee’s art seems to inhabit that season permanently. Through every bull charging across the page, every child sketched with trembling affection, and every soft, earth-toned landscape, he continues to express a sentiment that resonates across generations: that even in hardship, life holds moments of luminous, aching beauty.

In this sense, Lee Jung-seop did not simply paint autumn’s colors; he painted its soul. And that is why, nearly seventy years after his passing, Koreans still speak his name with enduring warmth, as if he were a season returning every year—familiar, fleeting, and unforgettable.

SayArt.net

Maria Kim sayart2022@gmail.com