SEOUL — For more than two decades, Roh Soh-yeong, the director of Art Center Nabi, has been known in Korea’s art world as a visionary pioneer — a champion of media art, digital experimentation, and the dialogue between technology and creativity.

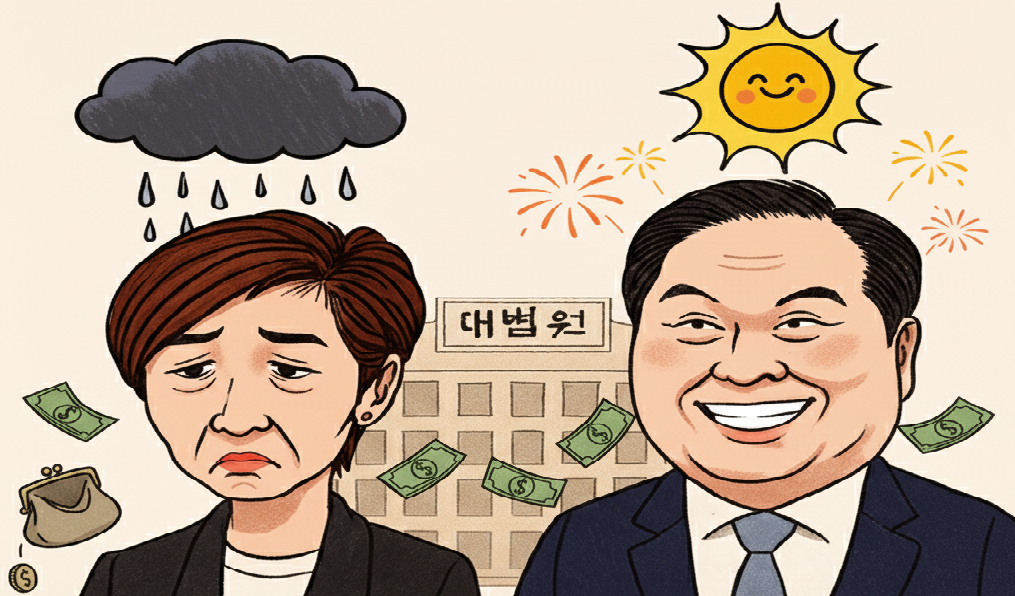

Now, her name has returned to the headlines under very different circumstances: as the central figure in a Supreme Court ruling that overturned a 1.38 trillion won ($973 million) divorce settlement against her former husband, Chey Tae-won, chairman of SK Group.

The court’s decision on Thursday not only reshaped one of Korea’s most publicized divorce cases, but also exposed how questions of wealth, power, and cultural identity converge in the country’s modern elite — a world where art, politics, and conglomerate legacies often intersect.

An Art Leader at the Crossroads of Power

Roh, 64, is the daughter of former President Roh Tae-woo and one of the few art leaders in Korea who has bridged corporate patronage and experimental culture.

As director of Art Center Nabi, founded in 2000, she helped bring digital art, new media, and interactive installations to mainstream attention in Korea — long before NFTs or AI art entered the global conversation.

Her initiatives at Nabi — including collaborations with international artists, technologists, and institutions — positioned Seoul as an early hub of media art discourse in Asia. For many in the art community, Roh represented the progressive face of cultural innovation within a traditionally conservative establishment.

Yet, her personal life has now been entangled in a legal battle that forces a different kind of reflection — about what happens when artistic ideals meet the realities of power and inheritance.

The Court Strikes Down a Record Divorce Settlement

On Thursday, the Supreme Court of Korea overturned an appellate ruling that ordered SK Chairman Chey Tae-won to pay Roh 1.38 trillion won as part of their divorce settlement.

The court found that the alleged 30 billion won in slush funds said to have been provided by her father, former President Roh Tae-woo, could not be recognized in asset division because they constituted illegal enrichment.

“Even if former President Roh provided 30 billion won to SK founder Chey Jong-hyun,” the court said, “such funds originated from bribes during his presidency and thus fall outside legal protection.”

With that reasoning, the justices declared that illegal or unethical funds cannot be taken into account in property division, emphasizing that “antisocial and immoral conduct is beyond the law’s protection.”

Roh, who had argued that her father’s support symbolized her own contribution to SK’s growth, saw that claim invalidated.

The decision nullifies the record-breaking settlement but maintains the 2 billion won ($1.4 million) in alimony previously awarded.

A Legacy Entangled in History

For art observers, the case resonates beyond family law.

Roh is both the daughter of a former authoritarian president and a cultural innovator who has sought to reframe Korea’s art ecosystem through openness and experimentation.

Her personal narrative — as a woman balancing political heritage, corporate marriage, and artistic vision — reflects the complex negotiation between power and creativity that still defines much of Korea’s cultural landscape.

Roh’s father, Roh Tae-woo, was convicted in the 1990s for receiving hundreds of billions of won in illicit funds during his presidency. The Supreme Court’s recent decision reaffirmed that those funds remain tainted by illegality, even when invoked decades later in a civil proceeding.

In essence, the ruling severed any symbolic or material connection between the political fortunes of the past and the economic present of SK Group — a line that also separates Roh’s artistic identity from her inherited one.

Between Art and Aftermath

While the legal spotlight may dim, Roh’s impact on Korea’s art scene remains significant.

Under her direction, Art Center Nabi has championed artists exploring AI, robotics, sound art, and digital interfaces, serving as a bridge between the tech industry and creative experimentation.

The center’s long-term collaborations with companies like SK Telecom and with global partners have helped position Korean media art on the international map.

But the irony is striking: the same corporate world that supported Nabi’s growth is now the source of her most public conflict.

In a society where art and conglomerate power are often intertwined — through sponsorship, philanthropy, and influence — Roh’s case highlights the fragility of those relationships when personal and institutional histories collide.

An Uncertain Future, A Lasting Cultural Footprint

The case will return to the Seoul High Court for reconsideration, and the final outcome remains uncertain.

Yet whatever the legal conclusion, Roh Soh-yeong’s cultural significance is unlikely to fade.

Her legacy as one of Korea’s first curators to bridge technology and art, her influence on younger media artists, and her ability to navigate between the worlds of privilege and experimentation remain hallmarks of a complex but undeniably pivotal figure.

The Supreme Court’s ruling may have ended a financial dispute — but for Korea’s art world, it reignites a larger conversation:

How does an artist, or an art leader, maintain integrity and independence amid the gravitational pull of power?

SayArt.net

Jason Yim yimjongho1969@gmail.com